“Anything is possible when you get the right attitude.”

Over the past few years, I’ve built different healthy habits. One of them is getting out of the house every single morning, no matter what – for a run or at least a walk. That’s when I decompress, reconnect with myself, and let my intuition guide my next steps. By now, the team knows not to have a serious conversation with me before I’ve been out; otherwise, I might just react in a way I’ll regret. ;)

On this particular Saturday during my walk, a young girl called me into her field. She said, “Madam Maria, I want to tell you something.” I didn’t recognise her at first, as we are working with so many children at the primary and secondary school – around 250 kids. Her name is Hadija. She said, “I’m very happy because now my grandmother is okay. She had ulcers, but when I tried the blackjack you taught us, she is now feeling very good. Everything you taught us, we tried it.”

I can’t tell you how this little, unexpected moment lit me up.

On another walk, I met two girls from the secondary school who were collecting plastic bottles. Curious, I asked them, “What are you doing?” To my surprise, they replied, “We’re collecting bottles for the garbage bin we’re building together with you.” We regularly give the children tasks after school, like collecting bottles, but at first, they didn’t always follow through.

To actually see the direct impact in these children’s daily lives is insane. Yes, in our processing club led by Samuel Nyanzi, director of RUCID, we are focusing on creating big, sturdy garbage bins out of plastic bottles that can also be marketed.

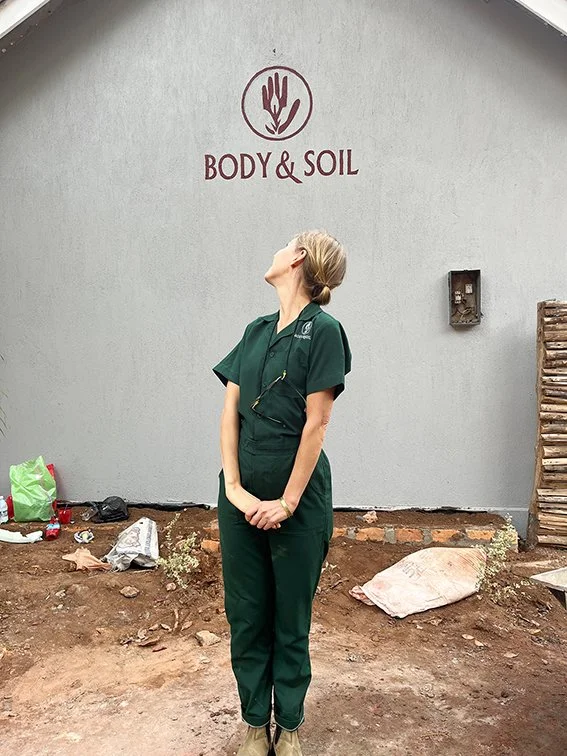

Because the truth is, you can plan the most perfect garden bed, but if you lack natural fertilizers, don’t have enough mulch to protect the soil, and are surrounded by garbage, your efforts won’t succeed. One reason for the large amount of waste is a lack of knowledge about waste disposal. But it’s also simply because there are hardly any garbage bins in rural areas. While we are currently renovating the B&S building complex, this is a challenge I face every day because the workers just throw their trash on the ground and walk away. They don’t even notice it. That’s why we need to find solutions that raise awareness, involve the next generation, and encourage them to be creative. We know that the children take what we teach them back home – and that’s how the cycle begins.

Another challenge these schools face – like many across Uganda – is not having enough income to afford even simple things: food, garden tools, paying the national water bill, or buying kitchen utensils. If any school is going to copy what we are doing, they will also need solutions for creating income.

Ultimately, this should come from healthy products, but what can schools do from the start to strengthen themselves? We are right in the middle of experimenting and finding solutions, but I’ll tell you more about that next month.

As a team, we sat down and asked ourselves: what are our findings from the last few months working in two community schools? If we started from scratch in a new school, or if someone asked us for advice now, what would we say?

First of all, the foundations would be:

Find out what you already have growing in your garden. What can you eat or utilise that you’re not seeing?

Clean your garden and get rid of garbage.

Start establishing natural fertilisers such as vermicompost or compost.

Grow more plants for mulching.

Then plan your garden.

With our three clubs (nutrition, agriculture, processing), that is exactly what we are doing!

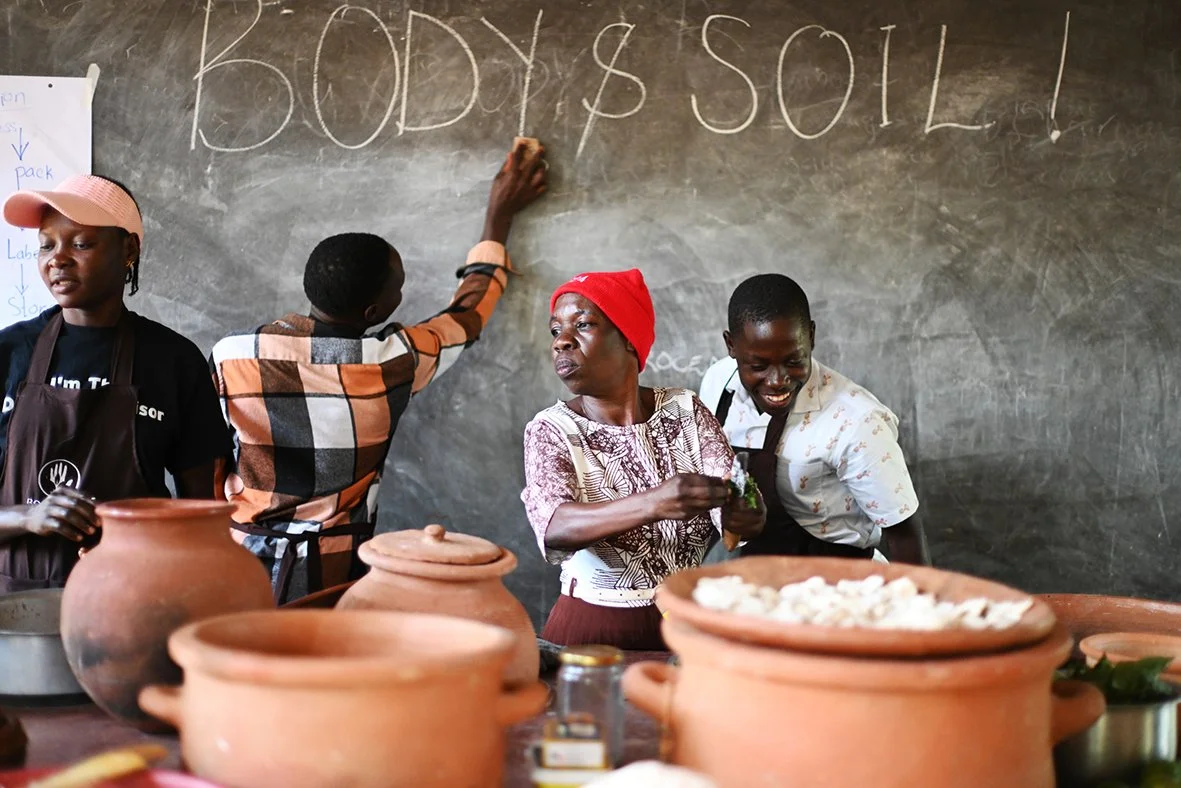

The next issue is the cooks. If they don’t know how to prepare what we’re growing, the food will just rot in the garden. That’s why Kalefu, our BODY&SOIL chef, cooks with them – from soil to plate.

For starters, what schools can copy is learning how to stretch the food they already have. For example, if they have beans, then Kalefu teaches them how to add cabbage, carrots and other greens they are not familiar with into the bean sauce.

Cassava is growing everywhere, and although in many parts of Africa the leaves are eaten as a staple, here they are not taken into consideration. That’s what I mean by seeing what’s available. We struggle with the same challenge at RUCID College ourselves. It’s embarrassing for everyone here that we mostly eat posho and beans for lunch, despite living on a property where everything can grow.

I believe that if we can’t change the diet here at RUCID, we won’t be able to change it anywhere. We are the example, and we have to lead. This week, something changed at RUCID and I saw it on our plates. All of a sudden, we had different types of beans, different tubers, always greens. I asked RUCID program manager Sarah, “Is this just by chance, or what is happening?” She told me she is trying her best to reorganise the menu, adding, “Anything is possible when you get the right attitude.”

BODY&SOIL brought in a local trainer for a workshop on processing local flours, but what I loved the most – and what stuck with everyone – was when we went into the garden to pick greens and ended up with 30 different leaves (wild and cultivated) in one basket. Up until now, mostly only three of the same greens are prepared. Everyone couldn’t believe it.

And this is what will make BODY&SOIL sustainable. Every single person involved in building these structures needs to see and believe what is possible before we can move further. The trainer also taught the team how to make a local stock. The stock people buy here is a highly processed food. It’s the local “Maggi” called Ryco.

“Everything is locally available,” Bonny tells the children as our trainer shares what he just learned: extracting cassava starch and mixing it with garlic, ginger, and turmeric to make a natural Royco. All of these ingredients every one of these children can grow them in their gardens – plus, there is a huge market demand. No-one here cooks without Royco!

Here are just a few more highlights from the last six weeks:

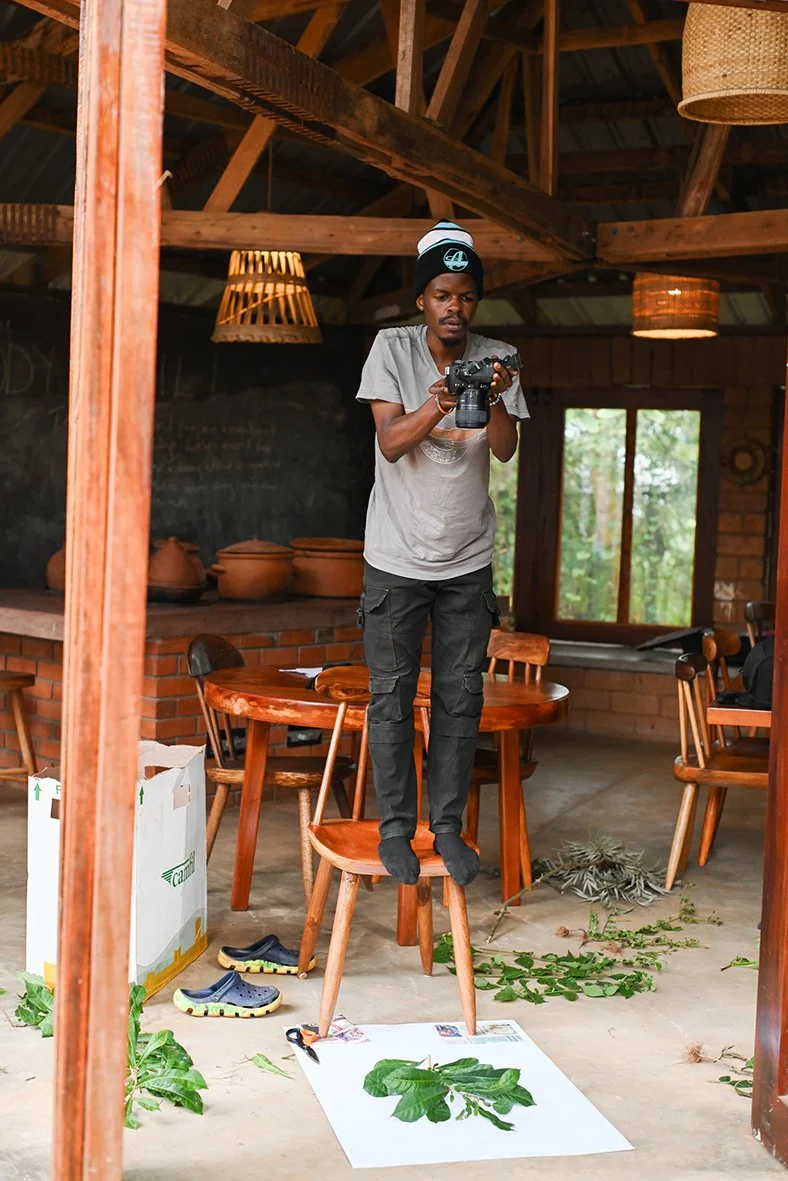

1. Joshua, a photographer, is on board to build and document the seed bank and healing herbs. His passion for herbs started with his final exam at Makerere Universtiy, where he documented healing herbs for malaria and got hooked. He explains best why he’s here:

“I don’t want to be part of the matrix – where you do your exam, you pass, but there is no continuity to your project. It ends with the marks and with a book collecting dust in the library. By engaging the community, it is a way to register the impact influenced by your project, so you keep the project alive.”

What he’s doing with his research – taking photos of every plant and seed, drying them – is not only laying the groundwork for a digital and tangible databank, but also for student workshops from Kampala to come here, which we are now planning for this year. All of this will create more visibility and broadcast indigenous knowledge.

2. Jojo has joined as a part-time expert in local foods and syntropic farming methods. Together this Monday, we will begin to lay the groundwork for a demo garden that mixes permaculture, agroecology, and syntropic farming.

3. Just this Friday, we presented our clubs to the parents, serving a banana cake made with local flours. We are already harvesting the first foods we planted, and kids are taking these foods home with them, so the parents have experienced this too. A highlight was that all our children wore their brand new B&S uniforms. More importantly, quite a few parents are coming on their own free will next week to be trained by us in sustainable farming methods. In exchange, we’re hoping to win these parents over to support us in the school gardens so they can become more productive, faster.

4. We are establishing documented herbal gardens for people to replicate with the students at RUCID. Our first garden includes a mix of local beans from our seed bank, along with spices and local herbs. Next week, we’ll work with a local herbalist to organise the garden according to specific healing benefits.

“You know you are turning things upside down – but in a good way,”

Bonny said to me after class. But what happens when I leave? The thing is, I’m not planning to for a while – at least not until we have structured things out. And even after such a short time working with the local team, I can see everyone already owns what we are building. Stuart, our B&S Project Manager, structures everything we do at the schools, not me. Kalefu talks to the community and comes back to me with suggestions on how we can solve problems. As a team, we sit together to decide what we need to do next.

When someone sees something not working, we question it, we discuss possible solutions, and then we try to implement them. When the time comes for B&S to expand, and for me to leave, it will change – because a person always leaves a hole – but does that mean it will change in a bad way? The structures we are setting are local, and they should be conceptualised by locals.

And it all begins with habits. Creating new habits in farming and nutrition. If you have ever tried to start a new habit you'll know, it takes time. It doesn't happen overnight, but gradually – or as my whole team and I remind ourselves every day, just 1% every day.

There’s so much more I could write, but I hope this inspired you to see the progress we’re making, born from a small idea and organically growing. If you want to know more, follow our Instagram for everyday updates. Stay tuned for our YouTube launch this year to learn more or even copy what we’re doing:)

Thank you for being here – and of course, send me a message if you would like to get involved.

Maria